That One ICML Tutorial That Changed How I Think About LLMs

I spend too much time on Twitter. But somehow, I've managed to turn my feed into something actually worth reading, especially for research updates. That's where I found this ICML tutorial called Physics of LLMs while working on my thesis. It changed how I think about language models.

Why It Matters

During my Master's thesis on autonomous agents, I started to get a weird feeling. In my previous thesis, everything was really research-y, in the sense that we had a clear hypothesis, a well-defined experiment, based on which we could confirm or infirm our hypothesis.

On the other hand, this thesis felt more like a product than a scientific writing. Yes, I wanted to show that autonomous agents are now possible and that current LLMs allow us to do stuff that was not really possible beforehand, although it might take longer and cost more than doing it by hand. But the point was not this, it was more like a proof of concept.

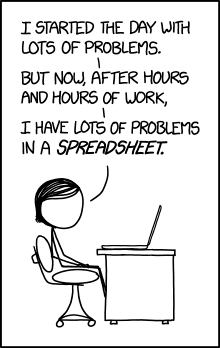

And still, I had the feeling this was not research. I just wanted to show that with this new technology, we have now more possibilities than before. And it's not like this was different than the papers I was reading at the time. Most of them followed the same pattern:

We wanted to solve this problem, we tried that and it worked, here's a paper.

And don't get me wrong, I am not saying that this is not research, or worthy of reading, I am just saying that I have a feeling that at least in this field, the definition of research or the approach to do research has shifted/evolved/changed.

The good part is, this rapid advancement in what we can do leaves room for asking the question: Why does it work? Why could we do that? And I guess, for me, that is a tad more interesting, but that's a personal thing.

Rethinking How We Study Large Language Models

In order to better understand what actually happens inside LLMs, we need to have a controlled environment in which to run repeatable, verifiable experiments.

Unfortunately, that does not work with internet-pretrained models—not because they are not good, but because we can't be sure of their pretraining and what they actually used as datasets (think of benchmark contamination, dataset quality, etc.). So we are left with using open-source models and pretraining the models ourselves.

Which now that I think of, is not necessarily bad. But I do think it will put more pressure on the so-called "GPU-poor," since your research will be directly tied to the availability of funds and hardware. But I guess this was also true before, right?

In any case, this has some implications. For the sake of simplicity and feasibility, we shall probably focus on the smaller models (like GPT-2, for example), which is fine, keeping in mind that our findings should be applicable to any LLM. We need our own pretraining + fine-tuning datasets. This by default is not easy, but it might be worth the trouble. And we need to be able to verify our findings. The experiments we devise and the hypotheses MUST be refutable—just like in any other high-quality research.

Interesting Findings

The tutorial is divided into three sections, each based on a couple of papers. I will not try to mention some of the findings that made me stop the video and say out loud, "What, that's crazy." Here it goes...

1. Knowledge Storage is Weird

A 7B parameter model can theoretically store more than Wikipedia. The entire English Wikipedia is about 50GB of text, and somehow these models can compress and store that much information. But it gets weirder—they found that models store exactly 2 bits per parameter, even when quantized to int8. This isn't just some implementation detail; it's a fundamental limit.

This has huge implications for how we build these models. Just making them bigger might not be the answer. We need to think about how to make better use of the storage we have.

2. Knowledge Has to Be in Pretraining

You can't teach models completely new things through fine-tuning. But if you include task-related data during pretraining along with general knowledge, it works well. Makes sense when you think about it.

This actually explains a lot of the weird behaviors we see in practice. Like when a model suddenly fails on a slightly different version of a task it was supposedly trained on. Or why some fine-tuning attempts just never work, no matter how much data you throw at them.

3. Models Can Detect Their Own Mistakes

When they give wrong answers, we can see internal signals showing they know something's off. They just can't automatically correct themselves. Kind of like when you know you're wrong but can't figure out why.

This is fascinating because it suggests there's some form of self-awareness in these models. Not in a sci-fi consciousness way, but in a measurable, technical sense. The model's internal state shows uncertainty before it makes a mistake. We can actually see this happening by probing the activations.

4. They Plan Before Speaking

LLMs build up an internal representation before generating any output. It's not just word-by-word generation. When solving math problems, for example, they seem to "think through" the solution before starting to write it out. We can see this by looking at their attention patterns.

This challenges the idea that these models are just doing sophisticated autocomplete. There's actual planning happening inside.

5. Information Access is One-Way

They handle information asymmetrically. They're good at questions like "When was Einstein born?" but struggle with "Who was born in 1879?" even though it's the same information.

This suggests that knowledge in LLMs is stored in a directional way—great for retrieving facts about known entities, terrible for searching across all entities for a specific attribute. It's like they build one-way streets for information.

The Bigger Picture

All of this points to something interesting: LLMs aren't just fancy autocomplete. They're doing some form of actual computation internally. The way they handle knowledge, plan outputs, and detect errors suggests there's more going on than simple pattern matching.

This matters because it changes how we might want to approach building and using these models. If we understand the fundamental limits and behaviors, we can:

- Design better training strategies

- Build more reliable systems

- Maybe even find ways around some current limitations

What's Next

I'm looking into how this connects to entropy sampling. The internal uncertainty signals might be useful for something I'm working on. More on that later.

I'm particularly interested in using uncertainty signals for better sampling strategies.

If you want to discuss any of this, feel free to email me. I actually enjoy talking about this stuff.

P.S. Hi David, I know you're probably the only one reading this at the moment! 😉

P.S. #2: Full disclosure - some of this content has been reformulated and corrected with Claude because I don't have the energy to fix my own typos or read this too many times. I write the ideas up to about 80% and set the tone, then let my friend Claude help polish the rest. Maybe in the future I won't do this, but that's how it is for now. 🤖✨

[ comments ]